Global bond markets have sold off recently due to uncertainty surrounding key political changes most notably in France and Japan. Japan’s Prime Minister, Shigeru Ishiba, resigned last week, which adds a potential shift in fiscal policy to concerns about slowing monetary policy normalization. Additionally, France’s prime minister stepped down recently after losing a confidence vote after trying to pass a budget with austerity measures. Add concerns about ongoing fiscal sustainability issues in the U.K. and debt and deficit concerns in the U.S. and it makes sense that longer maturity bond yields, globally, have risen.

France and the U.K. remain important buyers of U.S. Treasuries, so as their home market yields increase, U.S. rates look less attractive, which puts upward pressure on U.S. yields. That said, as we’ve seen in the U.S., particularly after the weaker than expected August jobs report, bond yields tend to follow the economic data. The Federal Reserve (Fed) is set to cut this week so we may be past cyclical highs. But with developed market debt levels expected to continue to increase with seemingly little appetite to reduce budget deficits, long-term bond yields may need to remain elevated to attract buyers.

Debt and Deficits: Not Just a U.S. Thing

While much has (rightfully) been made of the ongoing debt and deficit spending here in the U.S., the fiscal positions of major developed economies reveal profound disparities in debt management and long–term trend sustainability. Mounting government obligations could have significant implications on economic stability and monetary policy flexibility if not remedied.

Japan maintains the most precarious position among developed nations, with government debt reaching nearly 235% of gross domestic product () although net of the Bank of Japan’s bond ownership programs, debt/GDP is a more manageable 134%. This extraordinary burden has accumulated through decades of economic stagnation beginning in the 1990s, compounded by extensive government interventions including bank bailouts, insurance company rescues, and stimulus measures following the 2008 financial crisis, 2011 Fukushima disaster, and COVID-19 pandemic. Projections indicate Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio will remain near 250% through 2029, demonstrating the persistent challenges of fiscal consolidation under such extreme leverage.

The United States presents a different but equally significant concern, holding $37 trillion in government debt that constitutes roughly 30% of total global government obligations. At 122% of , American debt levels reflect substantial military expenditures, tax reductions, pandemic response measures, and structurally underfunded entitlement programs including Medicare. The current trajectory is on pace to be the largest projected debt increase among G7 nations over the next five years, though the dollar’s reserve currency status provides certain financing advantages unavailable to other sovereigns.

France registers concerning levels at 116.3% of GDP, positioning it among the Eurozone’s most heavily indebted members alongside Greece and Italy. The 3.2 percentage point increase in French debt ratios during 2024 signals accelerating fiscal pressures that may constrain future policy options. Moreover, with budget deficits close to 6%, debt levels are expected to continue to climb.

The United Kingdom maintains debt levels above 100% of as well, representing the highest ratio since the early 1960s following extensive pandemic–related borrowing. These levels present ongoing challenges for fiscal policy coordination and economic management in the post-Brexit environment.

Germany demonstrates the most sustainable fiscal position among these major economies, with debt representing 65.4% of GDP. Despite adding €57 billion in absolute debt during 2024, Germany’s debt-to-GDP ratio declined by 0.4 percentage points due to strong economic growth, illustrating how productivity and expansion can mitigate borrowing concerns when properly managed.

These divergent debt trajectories reflect fundamentally different approaches to fiscal policy, varying historical pressures, and distinct structural economic characteristics. The sustainability implications are important, particularly as elevated global interest rates increase servicing costs and potentially limit policy responses to future economic shocks. The management of these debt burdens will substantially influence global financial stability and long-term economic growth prospects across developed markets.

Source: LPL Research, Bloomberg, 09/15/25

When Political Instability Meets Fiscal Profligacy

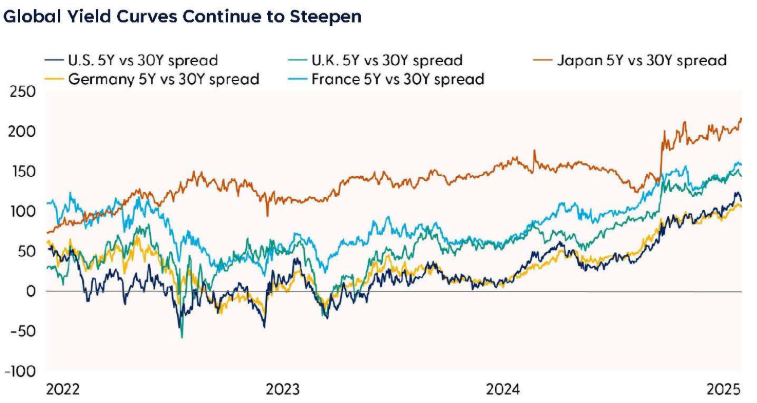

Elevated debt levels and political instability is a toxic cocktail that usually results in higher borrowing costs through an increase in sovereign term premiums. Term premiums represent the additional compensation investors demand to hold longer maturity bonds irrespective of growth and inflation expectations. And after years of negative term premiums, yield curve dynamics have shifted in many developed markets to reflect these growing concerns.

In Japan, the political landscape was rattled when Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba announced his resignation. His departure has triggered a leadership contest within the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), with internal elections anticipated to take place on October 4. However, the implications extend beyond party politics. The incoming LDP leader will need to secure a majority in the lower house of the Japanese Diet to form a stable government.

The new prime minister would then need to either form a broad coalition or call snap elections. The LDP is generally considered the more long-term-rates-friendly party by the markets, so failure to form a government could usher in a period of heightened political uncertainty, undermining investor confidence and amplifying volatility in Japanese government bonds. The Bank of Japan, already navigating a complex policy environment with inflation at the highest levels in the developed world, could also be forced into a bit of a holding pattern until greater political certainty is achieved.

Source: LPL Research, Bloomberg, 09/15/25

What’s This Have to Do with U.S. Markets?

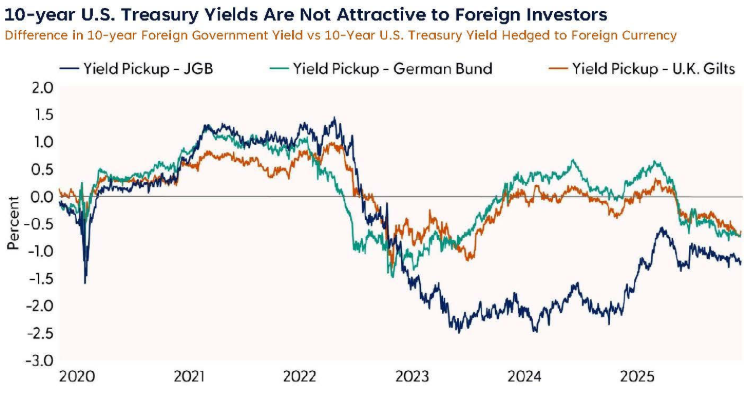

As noted, long-term interest rates have surged globally, pushing U.K. Gilts, Japanese Government Bond (JGBs) and German Bund yields to multi-year highs. And with the recent global selloff, longer-term interest rates are higher in many non-U.S. markets, which may mean foreign investors (which make up 30% of U.S. Treasury ownership) may not be as willing to invest in U.S. Treasury securities.

Non-U.S. investors, particularly from Europe and Japan, are increasingly dis-incentivized to own U.S. Treasuries on a currency-hedged basis due to rising home-market yields and high hedging costs. The yield differential between U.S. 10-year Treasuries (4.0%) and 10-year German Bunds (2.25%) or 10-year JGBs (1.10%) has narrowed as global yields have surged recently. For Eurozone investors, hedging via currency swaps involves costs tied to interest rate differentials, which reduces the effective Treasury yield below that of Bunds or even U.K. Gilts. Japanese investors face similar challenges, with yen volatility and JGB yields at 1.1%, making domestic bonds more competitive after hedging costs are factored in.

The potential reduction in foreign buyers, at the same time Treasury issuance is expected to remain elevated, may mean long-term bond yields remain elevated to attract buyers. But Treasury yields are primarily a function of growth and inflation expectations so as the economic data goes so goes Treasury yields. With the Fed set to cut interest rates this week due to a softening labor market, Treasury yields may be past cyclical highs. Indeed, recent Treasury auctions have been supportive of bond prices with some of the best end user statistics ever recorded, suggesting investors are eager to lock in current Treasury yields. But with developed market debt levels expected to continue to increase with seemingly little appetite to reduce budget deficits, long-term bond yields may need to remain elevated to attract buyers. We remain neutral duration relative to benchmarks and think the best risk/reward in the Treasury market remains in the two- to five-year parts of the Treasury curve.

Source: LPL Research, Bloomberg, 09/15/25